Behchokǫ̀

Travelling through thousands of years of history

Behchokǫ̀ means "Big Knife" in the Tłı̨chǫ language. With a population of about 1,900, it is the largest settlement in the region, the Tłı̨chǫ capital and seat of the Tłı̨chǫ Government.

Behchokǫ̀ has a long history as a gathering place. In the days of the fur trade it was an outpost of the Hudson's Bay Company, known as Fort Rae. Hunters and their families would make the long journey from the outlying communities to visit the regions only trading post.

Here they exchanged the bounty of their annual hunt for supplies needed for the next season. Pelts of beaver and marten were traded for tea, sugar, tools and ammunition. It was a time for celebration and an opportunity to reconnect with the larger community before returning to their individual hunting routes.

Today Behchokǫ̀ is a vibrant community that regularly hosts events, meetings, hand game tournaments and other festivities that draw in travellers from across the territory.

Transcript

Trails of Our Ancestors 2011

[A crowd of people cheer and take photographs as fully loaded canoes depart from the shores of Behchokǫ̀ at the start of the Trails of Our Ancestors annual canoe trip.]

Trails of Our Ancestors canoes departing from Behchokǫ̀ in 2011 on their way to the 11th Tłįchǫ Annual Gathering.

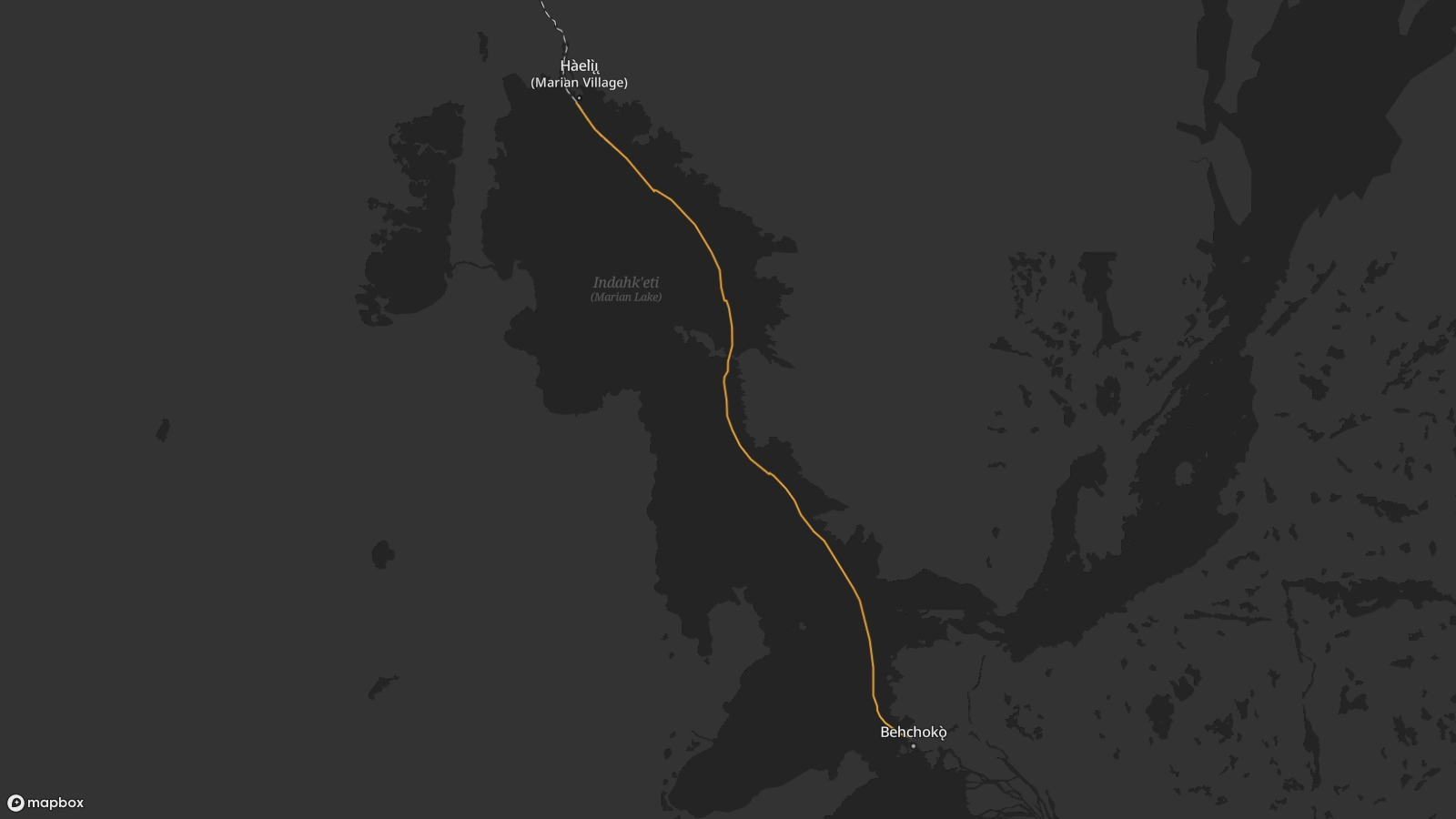

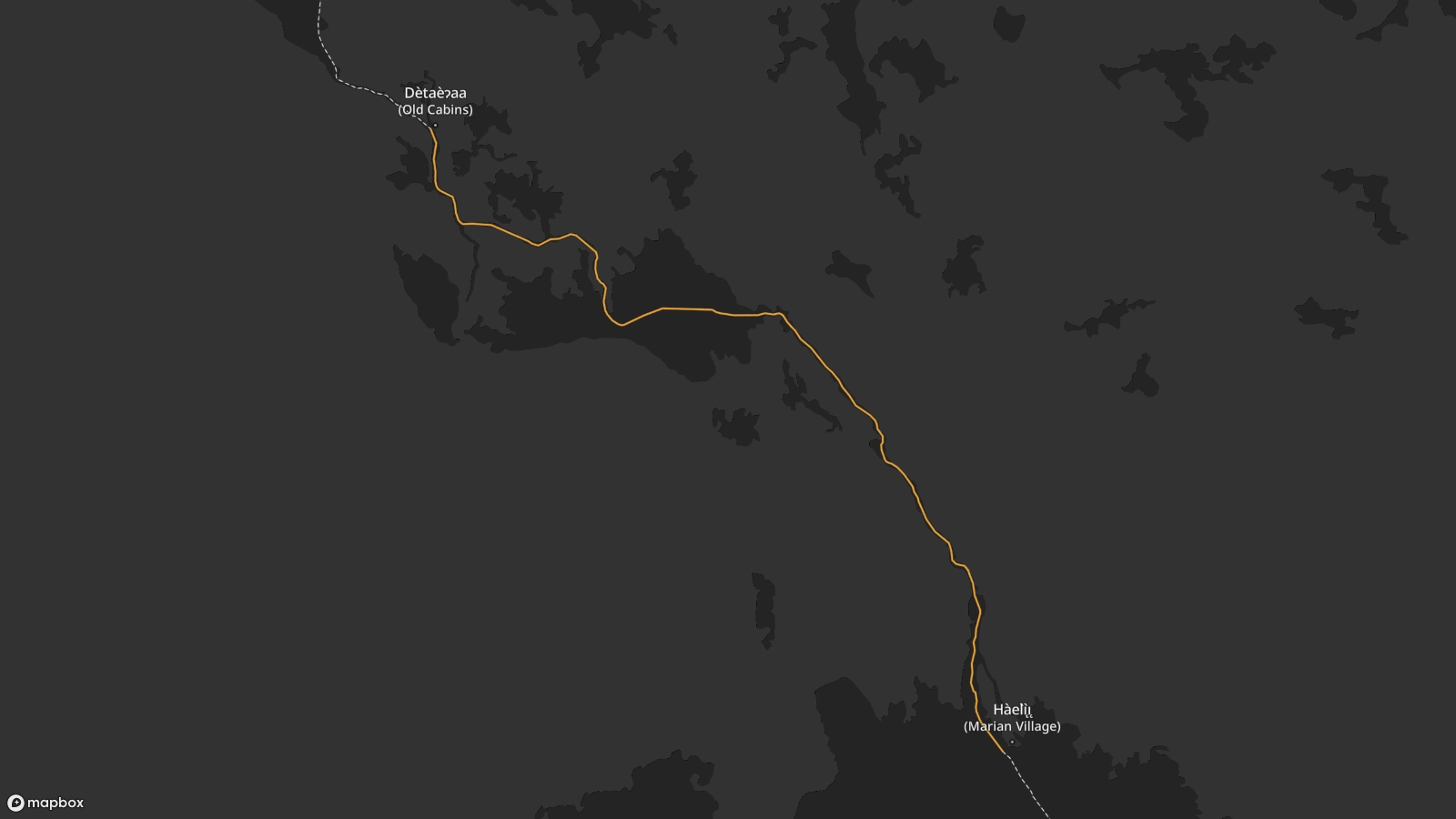

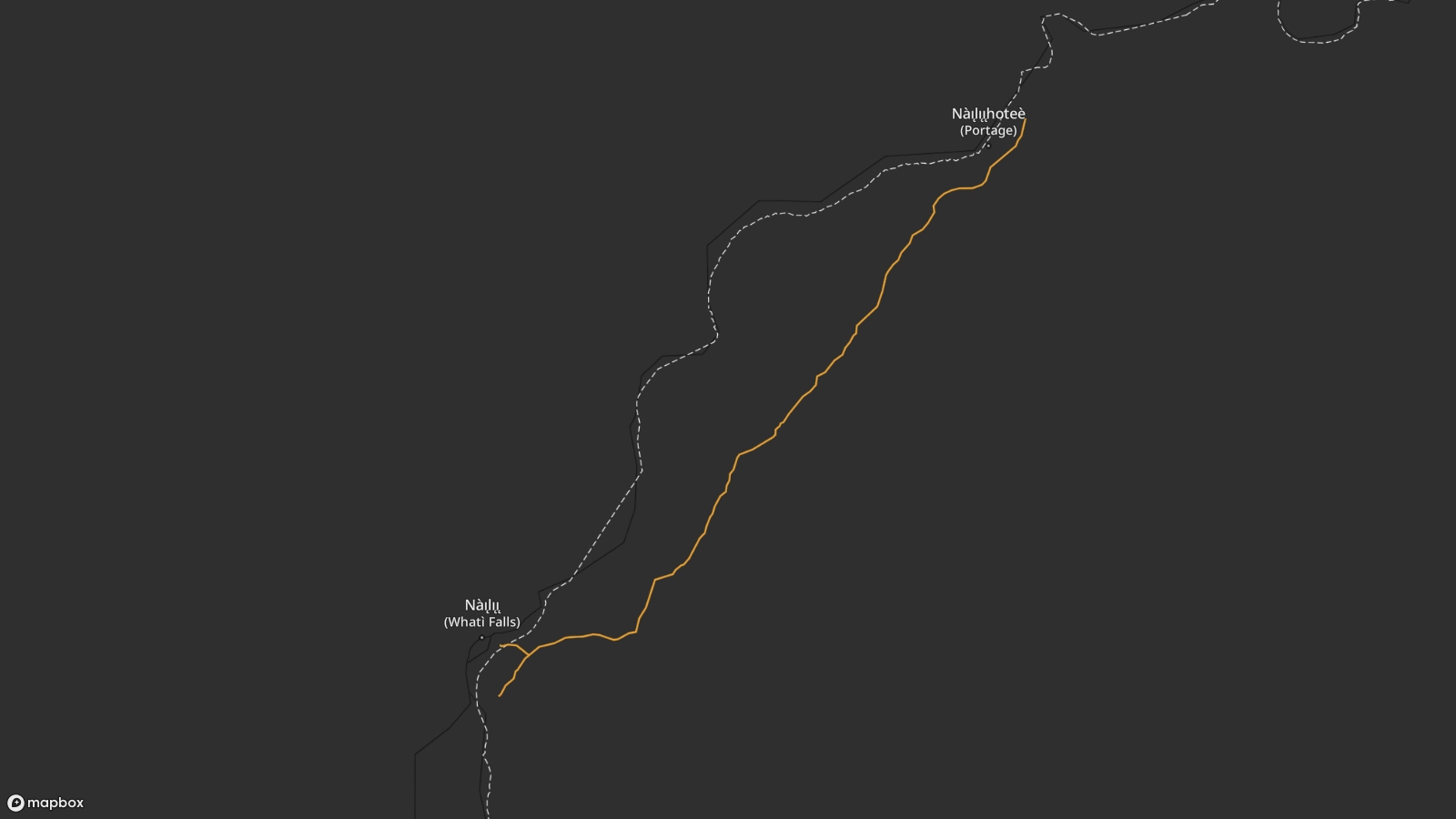

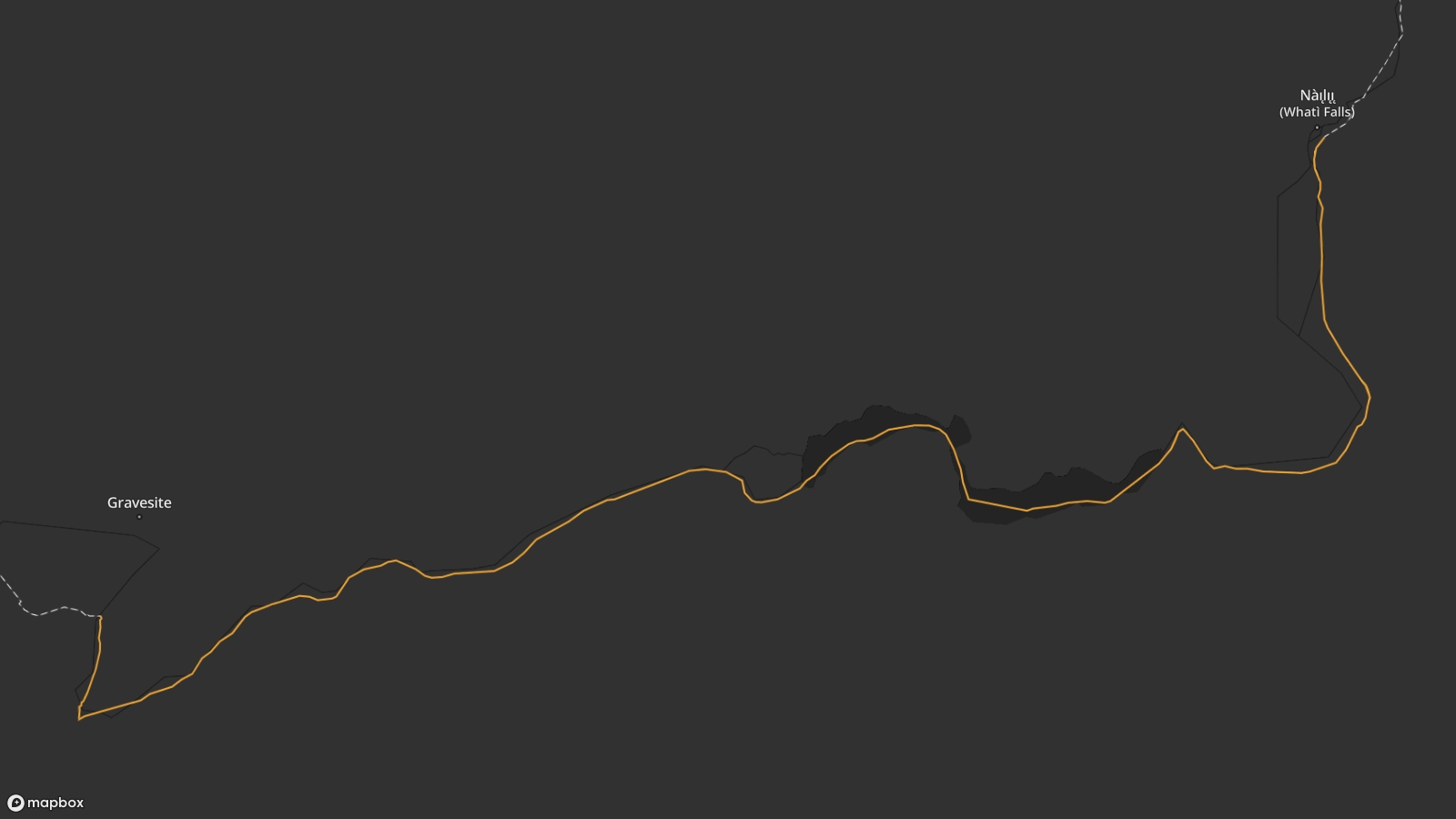

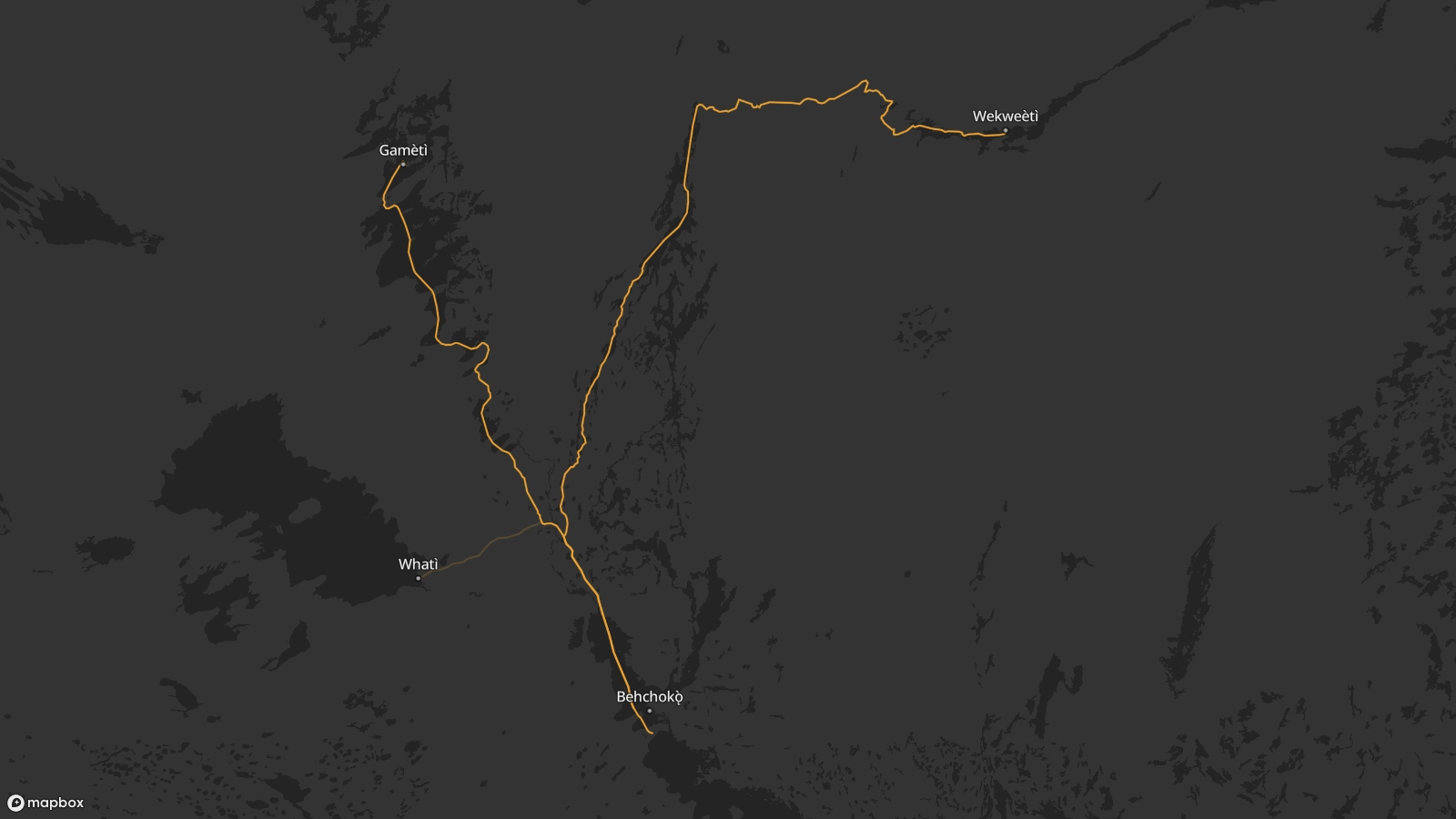

In 1994, the Trails of Our Ancestors program was initiated to pass on this ancestral knowledge and traditional practices. The first group paddled the 15-day journey from Behchokǫ̀ to Gamèti and arrived to a huge celebration as the festivities of the Tłı̨chǫ Annual Assembly got underway.

The program allows Tłı̨chǫ youth to retrace the paths and experiences of these trails through the eyes of our Elders. The boat trips have always been considered to be part of a vision by the Dogrib people to become “Strong like two people.”

“Like an armada, the incoming flotilla of canoes from the ‘Trails of Our Ancestors’ is a vision of pride for the Tłı̨chǫ, almost like an apparition of the Ancestors themselves. With many anxious to take their turn, the canoe trips are like a rite of passage for every Tłı̨chǫ citizen, and revitalizes everyone concerned.”

John B. Zoe

Transcript

The Power of Our Ancestors Knowledge

[A video interview with Tłı̨chǫ elder Jonas Nitsiza sitting at a table, with a bright window behind him. He is an elderly man with short white hair, wearing dark rimmed glasses and a blue striped button up shirt.]

Jonas Nitsiza: Now I’m going to tell you the story. The story I’m telling is the story to all of the people. I was born and raised here since I was young. I have been with Elders, by boat and went with them on a hunting trip. I participated with these Elders, I have always been involved with where they gathered and watched how they talked and shared their knowledge. I worked with them since I was capable of working with them.

Our ancestor’s knowledge is very powerful, very strong. I held onto Elders’ stories and kept holding onto their knowledge so if I’m asked to share if I can. There’s so much of their knowledge that I’m holding. I don’t want to let go of it.

Today they say there’s so much change from us, we hear about it. We cannot let go of our ancestor’s knowledge. If we let it go, we will not know where to go, we will have no direction. I don’t want that to happen, so I tell these Elders’ stories to the Youth. This story is to last with us, we are supposed to seek it out and to listen. Now it has reversed, this cannot happen.

As of today, those who hear me should try to do what they can about our ancestors’ knowledge. If a person wants to know or learn about our ancestors’ knowledge they have to visit the Elders and ask them. They will not say, “No!”, they will be happy. We can survive and strive forward. As people, we hope to not lose our stories of our ancestors. When we look at it, it looks like our land is empty and alone. I hope it doesn’t happen. Whoever has heard me should follow how I took our ancestors' stories and kept them. I thank those who have listened. This is what I had to say.

The Tłı̨chǫ landscape is known intimately to Tłı̨chǫ Elders. Names and narratives convey sacred knowledge, and in this way Tłı̨chǫ culture is tied directly to the landscape. The main focus on these trips is for the Elders’ to share their stories at these significant places.

To preserve this knowledge the Trails of Our Ancestors program focuses on sharing the Elders’ stories at these locations and passing down Tłı̨chǫ culture to a new generation.